…don't be a victim to—handcuffed to—an illusion of what you think life is. Don't be limited about your limited view of what life should be.

What is a human on the loop? Not just one more pseudo-philosophical phrase from a TED stage—but Silicon Valley’s bravest, or most brittle, attempt to define what makes us, us. There’s something uncanny in the confidence: wrap the user at the center of a digital feedback circuit, call that agency or ethics, and get on with the business of making the world more programmable. But if this “on the loop” construct feels to those with long memories like a dangerously thin summary of the entire human story, that’s because it is. Philosophy and theology have been mining this terrain for longer than any codebase, and with far less certainty.

Albert Camus, who held the tension between hope and resignation with rare clarity, said it plainly:

I have always held that, if he who bases his hopes on human nature is a fool, he who gives up in the face of circumstances is a coward. And henceforth, the only honorable course will be to stake everything on a formidable gamble: that words are more powerful than munitions.

In the context of contemporary tech discourse, that formidable gamble throws down a challenge: is this optimistic faith in “human on the loop”—the neat fix wherein a thin layer of human oversight tames runaway complexity—warranted? Or is it in need, urgently, of deeper skepticism, a rougher kind of realism?

Technology alone is not enough. It's technology married with the liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields the results that make our hearts sing.

-Steve Jobs

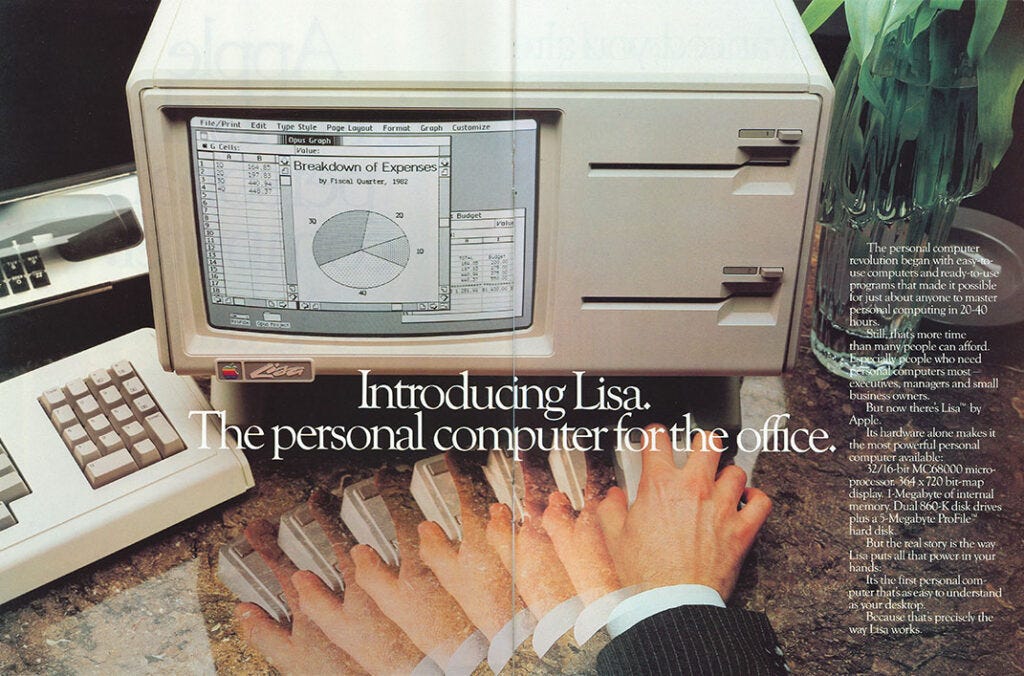

Let’s rewind to 1983. Apple launches the Lisa—nine thousand, nine hundred, and ninety-five dollars for a computer. Ten thousand units shipped, legacy secured. The graphical user interface quietly rewrote how humans encounter the machine. Suddenly there was a world of windows, icons, and cursors—an abstraction layer for the senses, a new symbolic vocabulary. If you wanted to track the real revolution, it wasn’t happening in the workplace. Look more closely. You’ll see the slow, almost unnoticed migration of perception into representation. This revolution was about humans adjusting so their minds could speak symbolically to machines, while the machines loaned their logic back in return.

But the “user” isn’t just codes and clicks. A “user” is water, salts, a storm of chemistry, layered feedback from mitochondria to cortex, a pulse humming in synchrony with the oldest rhythms of earth and sun. Perception itself is an abstraction machine—a filter for a world too complex and strange for anyone’s direct apprehension. Every new system, every tighter loop of information, is another invitation to believe that the model is the reality. It’s always tempting. It’s always a trap.

Despite its commercial failure due to the cost, sluggish performance relative to its hardware and some technical issues, the Lisa's innovation laid foundational concepts that influenced later computers, notably the Macintosh, which was cheaper and more widely adopted. This moment encapsulated a shift where machines began to "believe" something about humans—that their essential identity as users could be abstracted from their full embodied, chemical, and physical reality, creating a detachment between the "user" in the machine's terms and the person behind it.

Thus, while the Lisa's prohibitive price limited it to early adopters, it set the stage for a new conceptual and technical framework in human-computer interaction, where the machine engages humans as symbolic agents, separated from their full human experience. This separation, paralleling economic views of humans as rational agents (homo economicus), reflects a fundamentally new stance by the machine about human users, marking a culturally and technologically transformative moment.

Which brings us back to knowledge. It’s not the same everywhere. There’s the knowledge of doing—technique, system, certainty. That version feels solid, calculable: a computer can do it, or a lawyer, or a really good spreadsheet. But there’s another kind—a rough, relational, qualitative sense for life’s tangled fitness. “Organic,” Emerson called it, the kind of knowing that can’t be optimized or automated, the kind that doesn’t collapse when you call upon it in the real world. As Ben-Ami Scharfstein persistently argues, all symbolic human life testifies to powers lodged in every body—not just in artists—but in every living, learning being, be it bird making song, child drawing a figure, or human facing the unknown with the vocabulary of invention and tradition alike. We know by knowing recursively, always failing, always returning, always learning anew how to harmonize order and disruption.

A human on the loop cannot fit on a diagram, cannot be an administrator of an algorithmic system, nor a widget in a feedback circuit. There is real danger in thinking we can abstract the human condition down to system diagrams without hemorrhaging what’s essential in the process. Over time, this breeds a special new ignorance—the kind that takes deeper root precisely because it believes itself enlightened. Each time morality is programmed, the half that can't be programmed—its inward necessity, borne of struggle, suffering, and presence in a world that resists—gets lost, half-forgotten, or treated as “noise.”

The price of our individualism is now becoming manifest on every hand. Humility is now required in order to make room for a new start. The second lesson of our experience is the need for assumption of responsibility—responsibility for everything that we do. But for responsibility to have actual content it must be understood in terms of a larger conception of being human—a renewal, at last, of the dignity of man. Responsibility, in these terms, becomes Promethean. The life of obligation begins in the cradle and goes beyond the grave. How shall we teach ourselves this? We hardly know, but we must begin to try.

Marc Reisner’s Cadillac Desert (1986), a monumental work on the environmental consequences of water policies in the American West, provides a powerful metaphor that complements these reflections. Reisner forces us to confront what it means for human beings to live on a continent marked by garden spots, vast deserts, mountains, and declining natural resources. The original settlers, unlike many of today’s exploiters, might have lived lightly, respecting the land’s limitations and adapting to its ways instead of seeking to change them relentlessly. Reisner chronicles a history of exploitation: draining wetlands, poisoning return flows with agricultural chemicals, damming rivers, silt buildup, and a politics of water imperialism prioritizing short-term gain.

The American West thrives today—despite being, by strict definition, largely semi-desert—because tens of thousands of dams, aqueducts, and irrigation projects have moved water from where it is plentiful to where it is not, creating an artificial Eden at immense ecological cost. The price paid by nature—vanished wetlands, dead river deltas, ruined croplands—is immense and growing. According to recent scientific assessments, nearly 76% of streamflow in this region is appropriated by humans, with projections suggesting this could reach 86% as populations double.

This ecological fiasco mirrors the false optimism embedded in the “human on the loop” concept: the belief that systems can be engineered, controlled, and adjusted with a thin veneer of human oversight. Deep, systemic contradictions and limits are often ignored, just as the ecological realities behind the infrastructure of the West are obscured by political and economic hubris. So, there is a tension between human aspiration and reality— and this is reflected in an age-old cultural conversation

We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.

-Kurt Vonnegut

At the heart of all human endeavor to shape meaning through words, images, and symbols, lies the enduring technique of storytelling. Storytelling draws upon the universalizing impulse in art: the desire to see ourselves, to find our own reflection in every act of expression. Yet this urge has its shadow—a double edge—because every universal inevitably collides with the irreducible particularity of living and making. Story itself emerges from the stack of psychotechnologies that have integrated the human being’s unique role as a kind of living frontier: we are suspended perpetually between past and future, between light and dark, and we have woven that tension through centuries of cultural conversation. Philosophy, myth, art, and science all bear witness—from ancient hymns riven with the split of day and night to the modern quest to bridge consciousness and matter. Duality is not just an image; it is the archetype underlying our very thinking: knowing and not-knowing, self and other, hope and despair, presence and absence. This ongoing tension constitutes the elemental pulse of our perception and the drive behind every narrative, each alive with its own sparks, ruptures, and reconciliations.

It is in this tradition of cultivating technique within the creative tension at the heart of perception that the ego learns to serve the greater flow rather than attempting to dictate its course. To dissolve the fear of mistake and to embrace fully what surfaces is to participate in a persistent act of renewal—an improvisation that transforms the limited capacity of perception into an ongoing negotiation with the unknown. As an artist, Takahata shifts our gaze from assumed objectivity toward the inner landscapes of meaning and feeling—spaces where duality reveals both the tenderness and the rawness of the human spirit. His film Grave of the Fireflies, if one has not yet witnessed it, casts the duality between fact and experience into stark relief. Set in the waning months of World War II, the story follows siblings Seita and Setsuko as they struggle to survive amid ruins, grief, hunger, fleeting kindness, and moments of fragile beauty. From its merciless opening, the film discloses the characters’ fate and asks the viewer to dwell not on redemption, but on the flickers of warmth and hope that persist even amid devastation. Sibling love becomes a breath between heartbreaks—a pulse of potential remedy. The fireflies are luminous, brief, and inadequate; the children’s hunger is literal and existential. As with Reisner’s Eden—a garden won at the cost of loss—here, hope is both potent and perilous, exposed as tragic illusion if severed from the structures of realistic, systemic care.

And I began to realize that the only place where things were actually real was at this frontier between what you think is you and what you think is not you; that whatever you desire of the world will not come to pass exactly as you will like it.

But the other mercy is that whatever the world desires of you will also not come to pass. And what actually occurs is this meeting, this frontier. But it’s astonishing how much time human beings spend away from that frontier, abstracting themselves out of their bodies, out of their direct experience, and out of a deeper, broader, and wider possible future that’s waiting for them if they hold the conversation at that frontier level.

-David Whyte

Let us return to our programmatic human on the loop. By definition such a being, sentient and aware, must possess a tendency to make, use, and be made by symbols—the minimum groundwork of consciousness, as Nicolas Humphrey describes it. Symbols might be the primitive building blocks for humanity’s tendency to create art, which in its deepest form is always a negotiation between expressive spontaneity and inherited tradition—a movement both toward order and toward its dissolution. Read Reisner, watch Grave of the Fireflies, or live with feeling. You’ll see that hope without structure, art without audience, knowledge severed from lived feeling—these all descend into suffering, not salvation. Camus’s gamble on words must be tempered by sobering stories. Hope and words are potent, but they can be tragic illusions if untethered from realism.

So what, finally, is this loop? Is it only feedback, or do we dare include an ancient cosmology—what it means to belong to a world in ceaseless conversation? Are we not a wager of hope and failure, technique and mystery, language and silence? The best art does what the best systems cannot: it brings order into dialogue with chaos, intelligence with instinct, a knowing that both breaks its tradition and remakes it, endlessly. Duality is no parlor trick. It’s built into the meat, into the rhythms, into the immortal comedy of progress and disappointment. We are always caught between technique and meaning, between what can be administered and what can only be lived. Silicon Valley rarely admits that behind every dashboard is another human, chipping away at their “statues of perceived reality.” The model is never the thing; the feedback that matters is still the unsolved, unrepeatable feedback of consciousness against the world.

The truly real is born at the living frontier between what one thinks is oneself and what one thinks is not oneself—between desires and limitations, between the world’s demands and one’s own deepest voice. Humans are the living edge, the perpetual boundary where self meets other, and it is in this meeting that presence, vulnerability, and revelation arise. The human on the loop is not a technician, nor a mere overseer, or a ghost in the machine. We are Titans, makers of meaning, artists and children, always in danger of self-defeat, flawed and defiant, inventors of systems that will always exceed us in consequence. A human in the loop is a human condemned to consciousness, forced to suffer and delight in both the making and the breaking of all our inventions. The tools will always be impressive. The mysteries they cannot solve will continue to be our measure.