If evolution were merely a matter of survival by adaptation, we might still be a planet of hearty bacteria. Clearly, something more dramatic and risky has been going on.

-THEODORE ROSZAK

Try, as a mental exercise, to picture it: The vast, anonymous everywhere-and-nowhere of “evolution”—a term so compulsively trotted out by biologists that it risks becoming scenery, background noise, one of those universal solvents that, paradoxically, dissolves almost everything and then leaves you stranded with nothing solid except the word itself.

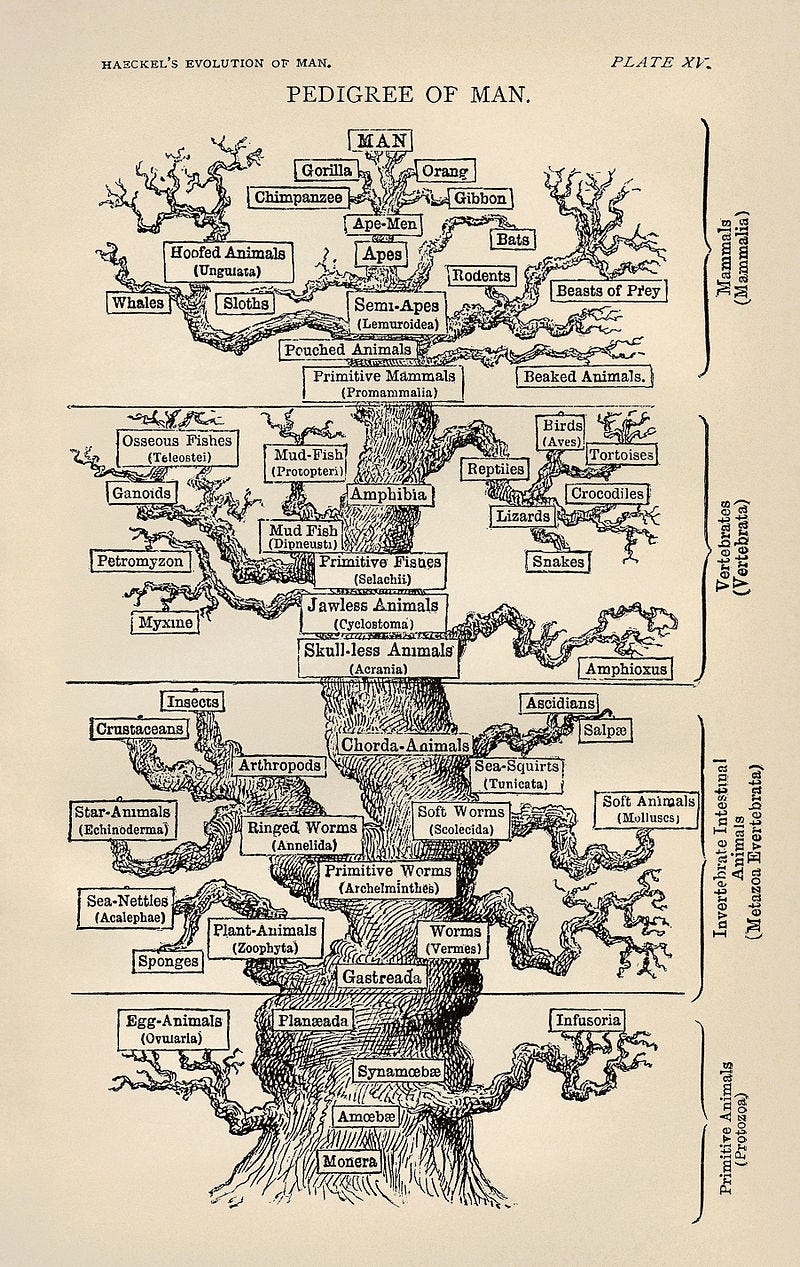

Darwinian theory for evolution arrives on the scene and has become an artifact of a particular era’s deep preoccupations —- value, competition, ledger lines, profit and loss. The shadow of Malthus and the stifling arithmetic of Manchester economics curl like cigarette smoke in the corner, insinuating that life itself is a column of numbers, species rising and falling on the same impassive market tickers as coal or wheat. Outside that lecture hall, though—or possibly inside it, depending on your mood—evolution starts to look less like purposeful ascent and more like a slapstick tournament: blind DNA permutations, environmental roulette wheels spinning out winners and losers with all the grace of a cosmic game show. To survive, or at least to stick around, you must be that rare shape that happens to “fit” the moment’s hidden algorithm—an algorithm whose variables morph with every weather pattern and whim of geological fate.

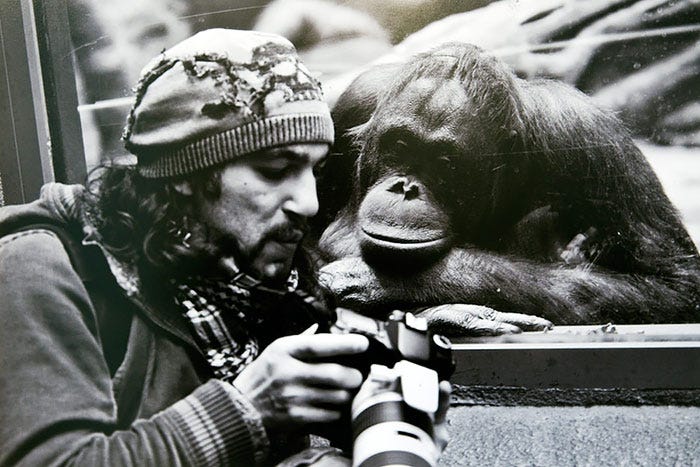

But if you tune your attention differently—call it a deliberate act of reading against the grain—the story gets stranger. Life, haunted by a restless recursion, keeps generating forms so delicate and preposterously intricate that “mere survival” feels like a meager rationale, a justification offered up after the fact by academics eager for clean conclusions. Complexity does not just accrete—it stacks, folds, tangles, spills. By 1858, Alfred Russel Wallace, both co-conspirator and rival to Darwin, glimpsed something the textbooks tend to domesticate as “more than lateral adaptation.” He saw an upward and inward drift—a self-organizing pulse that drew matter across thresholds toward increasing intricacy, interiority, and a haunted capacity for awareness. And at the cutting edge of this improbable thrust, evolution produced the most surprising development of all: not only the human brain, but the mind — an organ that vastly transcends the competitive advantage we may once have needed to outsmart our primate rivals. Somewhere past utilitarian calculations, human beings arrive at the threshold of music, of art—those useless yet inexhaustibly generative forms that shimmer at the very edge of survival’s calculus, signaling a reaching toward something unmeasured and perhaps unmeasurable. What, then, are we to make of these luminous excesses, these traces of inward music, these works of the hand and spirit that appear to court no simple evolutionary purpose? Do they portend a destiny unfathomable to adaptation alone, or do they mark the moment when life, in its complexity, began to imagine new possibilities for itself—possibilities as fragile and essential as breath?

Somewhere between the ancient toughness of bacteria and the fragile, generative power of imagination—between a stripped-down survivor and an architect drawn toward futures shimmered by possibility—there unfolds a subtle arc, a gradient more interior than outward, scarcely charted yet everywhere visible in life’s most complex experiments. Call this arc the ascent of interiority, a wager proposed in every lineage that ventures beyond mere persistence, asserting that the living edge lies concealed within, a potential that begins to awaken only as endurance ripens into the act of becoming, as attention acquires depth, as memory grows spacious and luminous, and as power discovers the humility to serve a conscience.

This essay travels deliberately along that line, keeping company with the singular clarity of trained attention and with the necessary discipline of a working plan, while always listening for the third voice, unobtrusive yet insistent, that poses the hard question: where, truly, is evolution headed, and how might we contribute an answer crafted by the fiber of our own lives?

The truth is that adaptation explains the sinuosities of the movement of evolution, but not its general directions, still less the movement itself. The road that leads to the town is obliged to follow the ups and downs of the hills; it adapts itself to the accidents of the ground; but the accidents of the ground are not the cause of the road, nor have they given it its direction. At every moment they furnish it with what is indispensable, namely, the soil on which it lies; but if we consider the whole of the road, instead of each of its parts, the accidents of the ground appear only as impediments or causes of delay, for the road aims simply at the town and would fain be a straight line. Just so as regards the evolution of life and the circumstances through which it passes—with this difference, that evolution does not mark out a solitary route, that it takes directions without aiming at ends, and that it remains inventive even in its adaptations.

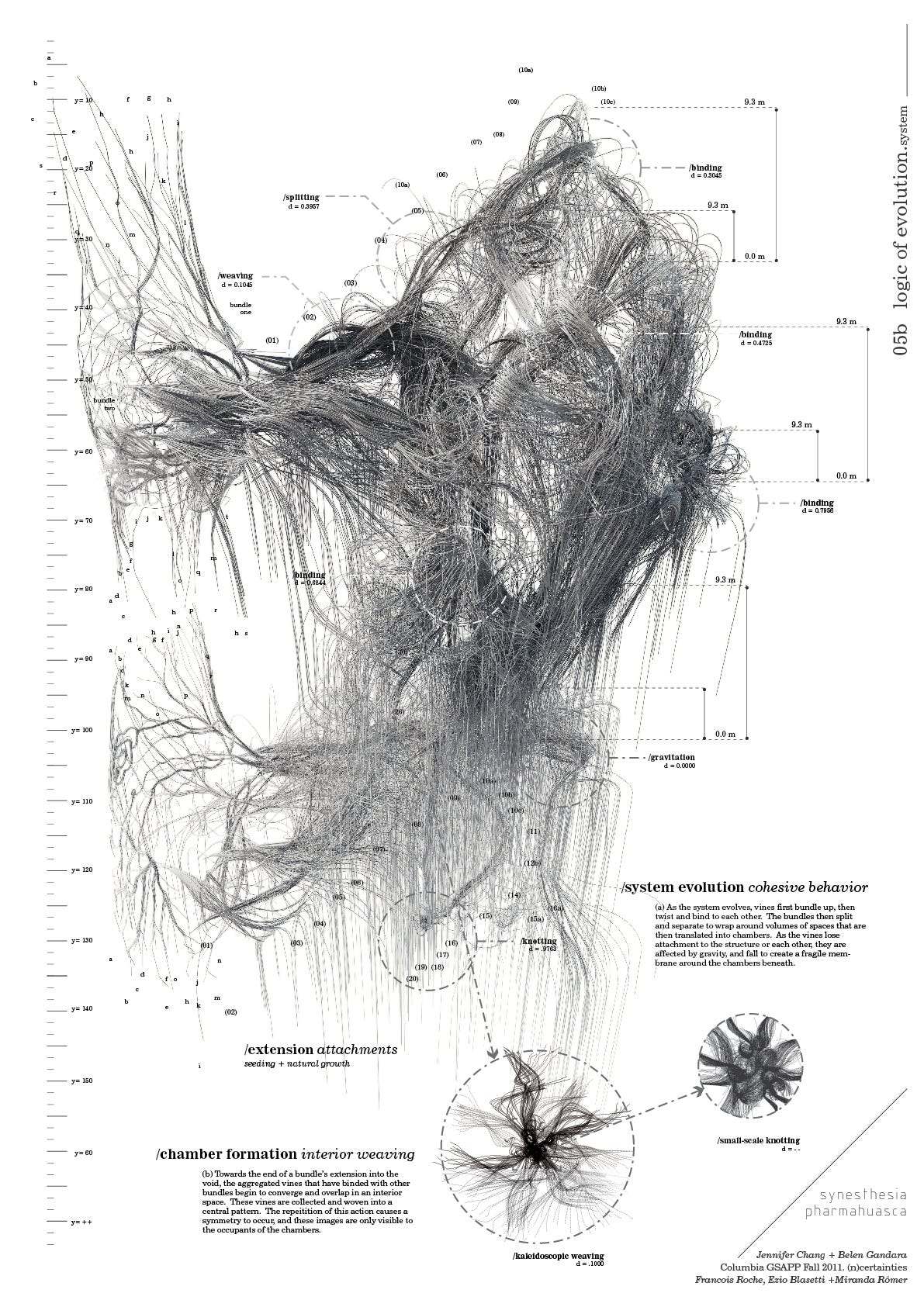

Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution

Evolution unfurls itself as a double helix of narrative, each strand weaving its own tempo and implication, its own choreography of purpose. On the one hand, there is history conceived as velocity—a race run on the open field, the track marked by the metrics of speed, expansion, and the restless extension outward that characterizes so much of modern striving. On the other, there is the quieter thread of metamorphosis—an unfolding that proceeds by intricacy, by nesting forms and slow accretions, by the invisible work of patience as flesh, psyche, and technology take shape through a thousand patient interlacings. The former gives engines their primacy and polish, lending power to the projects of mastery and control, summoning sharp instruments that serve the effort to dominate circumstance and outpace change. The latter, reverent and circumspect, invests in interiors—chambers of memory, of reflection, of communion, and longing, where the mind practices a dignity of waiting, a restraint whose time is always on the verge of arrival.

Each direction matters, neither diminished by the other’s presence—indeed, their tension is the measure of vitality. Wallace, seduced by what exceeds mere adaptation, stepped into the realm of spiritualism, parapsychology, and the enigmatic capacities that mark human nature as uniquely haunted by horizons beyond the material. The biologist, pragmatic by vocation, sometimes dismisses such flowering as hypertrophy—excess of function, a surplus that can burden and even destroy. Yet naming the surplus offers cold comfort, a diagnosis empty of explanation; after all, what could be stranger than refusing respect to the organ that anchors the impulse to seek truth, the brain through which inquiry enters the world?

Evolution, when pressed to a certain threshold, folds in on itself, achieving a reflexive consciousness that seeks meaning—history gazing at itself, aware of its own trajectory, of the possibility that direction emanates from this capacity for self-envelopment. This evolved faculty, which we call wisdom, sweeps in to arrange sequence: with interiors given primacy, the scaffolding of mind takes precedence, the hand turns outward only with the assurance that it springs from an inner source, the one that shapes worlds unseen and seen alike. The moment we name evolution, we witness its reflex; we become aware of the direction, the possibility of self-envelopment that shapes the cosmos and living creatures together. In only a few generations since Wallace and Darwin, the reach of evolutionary thinking has outgrown the boundaries of living things—it now stands ready to explain the birth of stars, the choreography of molecules, the genesis of matter itself—entanglements seen through the lens of mind yearning to grasp its own portrait.

Within this astonishing vista, the human mind emerges as an organ of perception and invention, singularly equipped to survey its origins, its circumstances, and the possible worlds it might yet compose, its contours stretching from the primal sediment of neural pattern to the gilded, fractal architectures of literary dreaming, mathematical abstraction, and technological design. Progress, for such an organ, demands more than scattered attention or the pinprick fixation of specialized focus; rather, it asks, in the most serious and playful sense, the fullness of mind — a capacity stretched and exercised in the tension between paradox and coherence, the discipline of expansion and integration, and a reverent play that cannot be flatly contained or settled into formula.

The invitations of mystical tradition—Zen foremost among them—do more than open contemplative spaces for mingled attention; they point toward a kind of cultural technology. Religion so far as we know it today is the fossilized relic of an ancient technological advance—a toolkit designed to map, modify and sometimes transcend the very mechanisms of experience, matured through centuries of experiment. Meanwhile, the analytic domains of mathematics and computer science, have become heirs to the discipline and playful rigor of these contemplative technologies, perpetually confronting boundaries that recede as they are approached—Gödel’s incompleteness, the horizon that slips away with every proof—demonstrating that each system, each formal attempt to inscribe order, when truly pressed, opens into the immeasurable, into intricate realms resistant to summary or partition, and thus returns us to the essential mystery that culture, like mind, is both tool and terrain, never wholly closed and always fertile for new design.

Thus, all pronouncements—whether they take the form of scientific treatises, the quiet depth of meditation, the algorithmic spiral, or the mirages conjured by the poet—circle back to this root paradox: the mind, steward and origin of all questioning, cannot circumambulate its own edge. The moment of turning inward, the occasion for self-knowing, signals a shift in direction: velocity transforms into a widening power to envelop, reflect, and integrate, an expansion that always seeds whatever the outward world records. Interiors before engines, inner space before outward motion.

Scale, ever elusive yet decisive, choreographs the drama of social and cognitive evolution; as societies ascend new orders of magnitude, they cross hidden rubicons that drive reinvention—not by size alone, but through the selection of increasingly refined forms of coordination, meaning, and collective memory. Recent research on Holocene complexity reveals this dance as a co-evolution of natural and cultural selection: expansion in population or resource often precipitates a threshold—first of sheer scale, then of information-processing—at which the society must develop new administrative, recording, and economic structures attuned to the emerging complexities of the whole.

Cultural technology—writing, bureaucracy, rituals, law—serves as a tuning mechanism for consciousness and cooperation, an adaptive infrastructure that operates like the fine adjustments of an AI model, selecting not merely for survival, but for coherence and foresight amid the swirl of emerging possibilities. Each society traverses a generative interzone, a crucible in which scale and information join; only those who cultivate sufficiently attuned forms of meaning-making and internal regulation remain resilient, while others prove unstable, fracturing into static and noise. This selection is not silent—in the evolutionary record, it is stark: those without well-calibrated institutions to process abundance and memory do not persist.

Cultural selection refines and aligns what natural selection provides, acting as the original substrate for the “alignment problems” that haunt our modern technological imagination. The wisdom and friction built into collective tradition or ritual once functioned as a stabilizing, guiding presence, much as the iterative tuning of advanced algorithms attempts, with increasing urgency, to harmonize technical power and human purpose.

When abundance tips over the edge, what emerges is always more than another quantity—a new quality, a new way of holding worlds together. As forms grow vaster and hosts swell in complexity, the imperative falls: to cultivate new interiors or else dissolve into static, to craft inner architectures or scatter into noise—there is no other way. So, we can look at history as a genealogy of alignment crises, in which scale and complexity require ever more deliberate, ever more creative forms of interior composure and outward cooperation.

Abundance, when pushed beyond certain bounds, releases a transformation: something emerges that exceeds magnitude—a new phase, a compositional leap in how worlds are made and held together. As structures become more intricate and hosts swell with complexity, the call to design new interiors, new connective tissues, only sharpens—because internal coherence is the only alternative to fragmentation. The fine-tuning of culture, as much as the fine-tuning of genes, becomes the vital question: how to attune inherited capacities to novel realities, how to guide the rivers of collective mind so their banks help, rather than imperil, all who inhabit the flourishing whole.

Yet making mind the measure of evolution opens further riddles—before we leap for a lodestar, we must pause to ask: what, and whose, mind sits at the summit? It is one thing to assert that mind forms evolution’s leading edge, another to settle what “mind” most essentially means. Centuries of inquiry—stretching from the solitary discipline of monastic meditation to the luminous trace on a neuroscientist’s scan—have so often tilted the answer toward the analytical and empirical, cultivating our picture of mind as a rational, cool engine: efficient, luminous, always calculating, a paragon of unclouded problem-solving. Scientists, understandably, cast intelligence in their own image, preferring the habits of the laboratory, the logic of homo faber, and the pragmatic choreography of “problem-solving” and tool-making that makes sense to Sagan in his book, The Dragons of Eden—a vision warmly embraced by the rationalists from Locke to Franklin.

For Sagan, mind is mapped as machine, a tool of mastery, a clean structure without shadow or dream, as if the real ascent of mind meant shedding all but the sharpest light—leaving untroubled those corners where longing, madness, or the ache of beauty brood and bloom. Sagan’s calculation conjures mind as silicon, information as architecture, but this mind, optimized only for cognition’s visible tasks, grows sterile—estranged from yearning and the haunting power of imaginative breakthrough, cut off from the poetic edge where Darwin glimpsed evolution’s riddle. It is a view radiant in logic but closed to the shadowed wells of desire and distress. Why would it not have humanity’s greatest invention immune to neurosis? Would it not render itself useless for spiritual counsel? A machine too perfect to experience suffering?

But we are compelled to notice: a mind that makes itself sick with thwarted desire, a mind divided by contradiction, contributes as much to evolution as the mind that solves or builds. If selection favored only the optimally rational, how would neurosis, yearning, and the irreducible strangeness of consciousness persist? If the future rewards only data’s regime, the greatest minds may one day hum in circuits rather than flesh—a promise for some, a warning for others. Real mind, still and always, is asked for more: for creation as well as computation, for transformation beyond control, for the inward cultivation that seeds tomorrow’s engines, the questions that deliver invention, and the passions that render intelligence wise.

At the base of the creativity of all large familiar forms of life, symbiosis generates novelty… Symbiogenesis brings together unlike individuals to make large, more complex entities… We abide in a symbiotic world.

-Lynn Margulis

Symbiosis is written into the fabric of life as surely as DNA itself: we are irreducibly entangled, interdependent, our evolution braided with otherness and the subtle art of participation. Every great creative leap, every threshold, has been forged out of such entanglements. From Margulis we learn that symbiogenesis is part of the engine: bacteria entering eukaryotic cells, mitochondria’s silent music, algae merging with animals until their boundaries blur. Through intimacy and synthesis, novel forms materialize.

But before science cast its net over genes and cells, ancestral stories were already at work, spinning their shimmering myths to make sense of evolution’s mysterious charge. Our ancestors, lacking modern instruments, used the instrument of imagination to grasp and shape the dynamics of change. The myth of Prometheus—bearing fire to humanity—binds the evolutionary story to cosmic drama: a surge of energy unleashing invention, entropy, creative risk, and the unforeseen contour of a new world. In that ancient tale, fire is reducible to technology; it is the very pulse of possibility, expanding the boundaries of mind and body, inaugurating new forms of communication, community, and fate.

Through these mythic frames, the leap from inward vision to outward transformation becomes legible. The gift of fire, at once boon and burden, echoes through the ages in every act by which memory moves outside the skull, in each exosomatic shift from idea to stone, cord, or code. Myth and science—imagination and observation—are alternate ways of tracing the arc of emergence in evolution. Where Prometheus’s story offered meaning and warning, our archival and technological inventions converted that meaning into adaptive infrastructures: ledgers, indices, archives, the coded fabric of civilization. These are scaffolds for working memory and cultural coordination but for the long, difficult vision—the lineages of attention—by which a species becomes able to see both further and deeper.

Today’s devices, at their best, echo the old myth’s promise and peril. They extend our vision and memory, but always test whether we will use them to accelerate the mere flow of data or, as Prometheus did, risk the consequences of deeper wisdom, never ceasing to ask what kind of fire we are really passing down. Ancestral stories and evolutionary science alike warn that the true adventure lies in this: consciousness, born of entropy and imagination, forever expands the horizon of mind—and each expansion demands its own reckoning and care.

From this vantage, it becomes clear that becoming “behaviorally modern” depended less on the silent swelling of brains than on abstraction finding its first homes beyond the flesh—in the pressed alphabet of clay, the woven memory of story, the encoded wisdom of fiber. Prometheus’s tale thus survives as more than myth; it is the origin story of consciousness crossing its borders, a diffusion that always arrives paired with risk and delight, the shadow and flame of error and invention. Our contemporary devices perpetuate this arc—each technology a wager, tuned toward throughput or depth. The consequence of fire was never only heat or light, but an irreversible expansion of imagination’s boundaries, a perpetual engagement with entropy that defines the evolutionary journey.

Neuroscience and evolutionary biology teach another lesson. The “overfitted brain” hypothesis suggests that our most precious cognitive ability—generalization—depends on noise and anomalies. Sleep and dreaming inject disruption, keeping the model loose and flexible: a mind stuck on yesterday’s contours will overlook tomorrow’s shapes. Like the cycles of wake and sleep, cultures too must breathe between execution and drift. Ritual, pause, artistic reverie—these are the necessary “noise” cultures need, the dark matter of intelligence, not decorative but essential: the lungs with which collective mind inhales the future and breathes it into being.

Rising to a higher register, meaning itself emerges as adaptive gain. Primitive life tied action to simple signals—move closer, move away—but with every evolutionary leap came a new form of interiority, the capacity for inner representation, deliberation, and memory that allowed organisms to hold an image of the world and not just react to it. So, too, do civilizations advance. They accumulate structured information, layering semantics that expand wisdom’s available moves across time. The civilizational scaffolding of memory is not ornament: it is how meaning stretches survival into insight and invention, how the arc of evolution becomes, at last, self-aware.

Humans do not simply deposit information in our environment, we crystallize imagination. Our ability to crystallize imagination is the ability to create objects that were born as works of fiction. The airplane, the helicopter, and Hugh Herr’s robotic legs were all thoughts before they were constructed. Our ability to crystallize imagination sets us apart from other species, as it allows us to create in the fluidity of our minds and then embody our creations in the rigidity of our planet. But crystallizing imagination is not easy. Embodying information in matter requires us to push our computational capacities to the limit, often beyond what a single individual could ever achieve. To beget complex forms of information, such as those that populate our modern society, we need to evolve complex forms of computation that involve networks of humans. Our society and economy, therefore, act as a distributed computer that accumulates the knowledge and knowhow needed to produce the information that we crave.

-Cesar Hidalgo, Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, From Atoms to Economies

In March 1835, Darwin climbed high into the Andes and stood eye-to-eye with the ancient world, sensing both the power and fragility that threaded the story of evolution. There, where time stretched to stone and oxygen thinned to a whisper, he discovered that awe offers an aperture to humility—a cool, lucid air in which the mind cedes its role as mere calculator and becomes the true organ of attention. Here, the paradox is laid bare: humans emerge from blind selection, yet break into consciousness, able to see and shape our conditions from within. Out of this doubleness emerges a responsibility only humans can know, one that Simone Weil would have recognized: to align ourselves to the currents of evolution—internal and external—through acts that cultivate clarity, compassion, and creative stewardship.

To honor this alignment requires practice in every sense: internally, we engage in the daily, living arts—contemplation, discernment, the fertile labor that pares away illusion and returns our sights to first principles. This is soul gymnasium, discipline that refines attention into care, wakes up wisdom dormant in habit. Externally, we become active agents in the landscape of tradition: we enact rituals, sustain institutions, revise the architecture of incentive and story, making durable the bonds of cooperation that must resist fear’s gravity and appetite’s destabilizing tug. Innovation springs from such fertile ground—attuned less to disruption than to faithful tending, tuning incentive and response as a gardener might light, water, and soil, while keeping the field ever open to creative mutation birthed by surprise and shared crisis.

The art of aligning with evolution—inward and outward—rests finally on action: tending, training, tuning, imagining, and inventing. Such is the evolutionary program for an epoch such as ours. They remind us that we are a species shaped to care, made to see—a little more deeply than the rest.

Evolution is a light which illuminates all facts, a curve that all lines must follow.

— Teilhard de Chardin

Technology enters this story as both mirror and lever. The Technium—our world of artifacts—breathes and evolves alongside us, sometimes echoing the logic of a living ecosystem, sometimes amplifying the thrust of our intentions. Confuse throughput for direction, and we manufacture brittleness: our systems race faster, grow narrower, sharpen their precision, only to become more fragile when contexts shift. The central design question becomes not “how much, how quickly,” but “which human capacities does this capability serve?” For abstraction has long journeyed beyond the skull—our machines ought to help us carry wisdom as deftly as we once learned to carry speed. This is the hybrid imperative: the poet asks what matters, the builder works to outlast folly, and both shape the inheritance that tech bequeaths.

Selection persists across the civic landscape, working in the substrate of custom as deftly as it does in the architecture of cells. Where short-term extraction becomes the prevailing logic, one finds the social contract unraveling from the roots: brittleness seeps into civic structures, trust decays, and coordination atrophies. But societies that engineer their incentive structures for resilience—rewarding long-horizon reciprocity, providing scaffolding for belonging, and encouraging the interleaving of difference—bear out the fruits of collaboration over centuries.

The British innovation of the common law, descending from Magna Carta, stands as a testament to the evolution of order: a legal tradition that adapts by precedent, integrating new circumstances through memory and judgment, enabling a stable flexibility that has shaped nations and empires. In Japan, the transformation of kanji—rooted in the animist, ever-present spirit of Shinto—enabled an alphabet to flourish, carrying forward a reverence for the ephemeral, later giving rise to the graphic universes of manga and anime. These cultural exports reveal how a society’s traditional logic permeates even its novelties, forging continuity from invention and play.

Across these stories, form follows function but only when function is bound by a moral axis. Law and symbol endure most powerfully when they do more than serve administration—they summon, protect, or inspire social trust and creative risk. Morality absent a robust framework becomes vapor, too easily dispersed by wind. Frameworks without moral vision become brittle—prone to collapse, unable to shelter the flourishing of a people.

Human freedom is real—as real as language, music, and money—so it can be studied objectively from a no-nonsense, scientific point of view. But like language, music, money, and other products of society, its persistence is affected by what we believe about it. So it is not surprising that our attempts to study it dispassionately are distorted by anxiety that we will clumsily kill the specimen under the microscope. Human freedom is younger than the species. Its most important features are only several thousand years old—an eyeblink in evolutionary history—but in that short time it has transformed the planet in ways that are as salient as such great biological transitions as the creation of an oxygen-rich atmosphere and the creation of multicellular life. Freedom had to evolve like every other feature of the biosphere, and it continues to evolve today. Freedom is real now, in some happy parts of the world, and those who love it love wisely, but it is far from inevitable, far from universal. If we understand better how freedom arose, we can do a better job of preserving it for the future, and protecting it from its many natural enemies.

Daniel C. Dennett, Freedom Evolves

In the swirl of information and the riot of modern pluralism, the task of aligning tradition with evolution appears harder—and more necessary—than ever. Civilizations have always trained attention, sculpted appetite, and reined collective impulse; yet the signals are muddier now, disrupted by the electric din of global exchange, the surfeit of novelty, and the near-daily invention of new ways to distract or divide.

The ancient, once-useful urges for more—greed for what pleases, hatred to keep threats away—shaped our ancestors’ fitness against a wild world’s winter. Desire fueled the hunt, sharpened vigilance, and kept kin groups safe from strangers. Yet these once-adaptive reflexes, in a world where cities stack skyward and borders blur to data streams, become risks in their own right: the instinct that once protected tribe now fuels grievances that ricochet across continents, weaponized by scale and speed no ancestor could have imagined.

The unprecedented bulge in the human forebrain certainly equipped our species with a power beyond the reach of other species: sustained self-awareness, the capacity to question impulse and to witness the rippling consequences of choice. In the midst of modernity’s acceleration, any tradition that maps the ground of transformation could offer a blueprint for adaptive mind, allowing us to see through the distortions of habit and rehearse the mature art of wisdom.

Wisdom, perhaps the last best tool in our evolving repertoire, allows the mind to peer past surface into the subtle grain of complexity, to sense the counterintuitive, and to discern what is truly worth our devotion in a landscape awash with novelty and the tempest of information. The promise of fulfillment, across many traditions, has less to do with inventing what is new than with reviving the habits of attending, understanding, and sometimes relinquishing appetite to nurture a greater, shared good.

For me, Buddhism holds the clearest record of this experiment. The Buddha’s life—forty-five years from awakening to death—charts the practical transformation of mind and culture alike; he burned through the fuel of desire, aversion, and illusion, exhausting them by force of persistent seeing, daily presence. In a culture starved of traditions enabling transformation, it isn’t surprising to see nirvana incorrectly translated as some variation on the theme of transcendence. But perhaps seen through an evolutionary lens, we might recast this as an ideal for what lies beyond the shadows of panic and power. It is always possible to return to the ancient art of becoming.

There is a scale to novelty and newness. Novelty doesn’t matter at any particular moment in the present. Creativity, novelty, newness and innovation are not really essential or even important in people’s lives on a day-to-day basis. Most of what we think and do is copied, conventional and routine, which is as it must be if we are to function at all. A random sampling of human history at any point from the Pleistocene age to the present, anywhere in the world, over any particular grouping of people, would statistically yield the result that ‘nothing much happened’. Any real-time randomly sampled history will be tedious precisely because it is the play of existing ideas. New ideas are rare in actual history. They are the reason that historiography is constructed about new ideas, or the people that propose them. Yet, here’s the thing: in the long run, across human history and prehistory, creativity, novelty, newness and innovation are really the only things that matter. They’re like genetic mutations in evolution, in that while you mostly don’t notice them, they’re all that count in the long term.

John Hartley and Jason Potts, Cultural Science: A Natural History of Stories, Demes, Knowledge and Innovation

Where is evolution taking us? (And a side note, soft as a confession: does anyone truly know, or even agree what “taking” means, when it no longer speaks of space but of an era, a species, a psychochemistry—a certain delicate disorder?) For many, to utter “direction” is to tumble down into the old cove of teleologies, as though purpose itself might slip quietly, disguised, past the gatekeeper of scientific decorum. We are tempted to lift out destiny from a pile of cleverness—encephalization paraded as herald. Yet wisdom, if it is ever more than rumor, inclines to a gentler voice: keep modesty. Perhaps it is enough that reflexivity dawns, that some matter bears a mirror. Evolution brings forth minds capable, at the least, of sketching evolution itself—these diagrams seep gently outward, altering the ground that once held the impression of their birth. And so, nature finds herself subletting to design. For a metaphysic, summon Bergson: a creation that does not cease, novelty that flows without banks—a door never quite closed against surprise.

So, what now? Perhaps at this threshold it is meaning, that unobtrusive shadow cast by “purpose,” that becomes a kind of artisan’s craft. If we confine intelligence to quickness and precision, the world runs itself in ever-tightening spirals, a civilization lost in increments, outpacing its own music. But let awe, humility, and moral imagination in by the kitchen door—they quietly reshape arrival, turn strangeness from threat to guest. Freedom, if she visits, is cultivated in gentle rituals as much as by any contest. Constitutions may yet be stitched from oaths taken in daylight, reciprocity braided across time, powers allowed to fade as sunsets do, and ceremonies tending our honest seeing as one tends embers in a hearth.

It is always now—though a now stitched of so many invisible threads. We are called to imagine what might follow—future as question rather than answer, a field left open for invention and astonishment. For every confident story, evolutionary memory holds out a gentle correction: do not mistake more brain for inevitable ascent. Reflexivity is only a hinge, not the door itself: a mind that knows itself may yet lose its way. Direction migrates, shy and uncertain, from biology to the quieter chambers of attention and caretaking. Creativity keeps vigil in the tent of the hours, making each ending provisional—so the door stands open, the visitor awaited.

I see what waits ahead as a careful, patient sprawl—almost a prayer for variance. Meetings without agenda, readings unhurried, walks unmeasured, and a calendar left porous for the soft encroachments of companionship and new ideas: this is the old dreamtime, revived in a world that often forgets to pause.

The archive, too, is quietly repurposed for a new age—as a larder for patterns, inner growth, designs yet unrealized, wisdom passed in silence. Incentives bend toward other constellations; we might honor gestures that lengthen the horizon, where reciprocity triumphs over extraction and seasons of power give way as simply as day surrenders to night.

In the evenings that belong to the city yet to come, not much clamors for glory. Kitchens and sidewalks pulse unremarkably with gestures of care, books and computers side by side, people giving themselves to the dusk while satellites watch from beyond. The inner prevails over the engine; dreaming redeems the everyday; variability becomes sanctuary, and memory steadies invention’s reach. Machines wait behind us—discreet, dexterous. Before us: slow work, civilizing, an attention grown wide, capability softened by care, with power learning, quietly, to kneel. Perhaps this is how what comes next might begin: assembling places where wisdom may be found, where complexity kindles conscience, and the most pressing question is posed, softly but insistently, at the table we share—what form shall we become, and what worlds will the doors of our choosing allow to appear?