Between Self and World: On the Art of Translation

Techniques for Living, No. 10

Welcome! If you found this article, or last month’s Techniques for Living to be inspirational, useful or interesting, I invite you to become a free subscriber to get more of Come to Mind.

Every human achievement, be it a scientific discovery, a picture, a statue, a temple, a home or a bridge, has to be conceived in the mind first—the plan thought out—before it can be made a reality. And yet, when anything is to be attempted that involves any number of ideas—methods of coordination have to be considered—the methods which have proven to be the best suited for such undertakings are models. We inhabit models of the world—cathedrals of thought slowly engineered toward realization. Yet not all of our building happens in the mind alone. Some of us, with a faith in the tactile, imprint the Latin root “manus” (hand) into each artifact, each manuscript: traces and textures that testify to the body’s ongoing invocation. Our hands inscribe the world with intention, as if to prove, again and again, that touch too is a way of knowing, a fragile proclamation against impermanence. And still, no hand has brushed the elemental fabric of life itself. Everything—statue, sentence, soul—is a translation, a mirage that glimmers at the edge of sense, a flicker of electricity and spilled light. Each moment arrives filtered, as if by sorcery, through the intricate lens of attention and imagination. The wide and ceaseless universe is always slipping away, neither thought nor language can reach it.

There is in human nature a peculiar faculty—a delicate thread that marks us off from mineral, plant, or animal alike. It is this capacity to bind ourselves to time, gathering moments as though they might become a garland of meaning, that confers upon us a quiet dignity. Yet even as we strive to fasten moments into story, a threshold appears: the architecture of certainty loosens, scaffolding dissolves into the blue air of uncertainty. Rimbaud murmurs his secret into this space: La vraie vie est absente. Nous ne sommes pas au monde.

True life is absent, always grazing the edge of what we can see, hovering just beyond the margins.

Living in any one place—inhabiting a life—brings sweetness and ache, joy and the subtle press of sorrow. All this, so easily leveled if we cling to it, demands another discipline. Sometimes wisdom looks like a kind of gentle detachment, watching feeling rise and dissolve, learning to yield rather than be ruled. What is hard becomes softer, what is narrow broadens; the shocks of living are eased into openness. At other times, practice is a subtle art of releasing: tracing the micro‑contractions of wanting and resistance, watching as they loosen and fall away. The world grows lighter, self and object and even time itself soften at the edges.

Neither art asks us to numb ourselves; both pursue the right proportions of feeling. Buddhist tradition invites a different stance: to listen with a deeper ear, to find where each feeling wants to be laid within the architecture of being. Translation is this kind of hospitality. Our hands, for all their longing to grasp, do not meet the kernel of reality—so the world, as we encounter it, arrives always already translated: mirage and memory, refracted through imagination’s patient lens. In touching, we only ever reveal the world so far; the rest is entrusted to the generous hush that lies between.

The piece of the mind that reaches this bright edge, that stands at the limits, must move with tenderness if it hopes to cross. To translate is to be loyal to sense and loose with sameness—to hold meaning but not force a perfect fit. We are asked to step softly, to lean into the mystery as translators: receiving what the world gives. The work is slow—the earth speaks in grounding syllables, the sky answers in long, lyrical lines. If meaning is to be found, it is made in this crossing—where we render rock and river, ache and astonishment, into the slow-growing language of possibility.

And this new idea we call meaning coalesces where the gaze lingers. It grows in the soft fibers of a particular looking. Sometimes the gaze thickens life to the point of difficulty; other times, it thins the veil and the world, unjudged, grows wide and weightless. Sorrow stirs dignity, presence dignifies sorrow, a strange, tenuous trust grows in the marrow. What is offered by that world is raw, unfinished—never wholly art, always material for attention.

Attention, washed clean by patience, reveals new textures in this world’s fabric. Memory shimmers, presence kneads out sharper forms, bringing the previous distances closer. In every act of translation, an offering is made—something is surrendered, but nothing is lost. All, in time, is returned to the open field.

Sometimes a life is spent beside the same question, curled intimately around a mystery, learning its inflections by heart. Years might pass with the same person, the same sorrow, even the same landscape—yet their true weather remains lightly veiled, just beyond reach. The devotion of attention guides us, but never permits complete arrival. It is precisely this unfinished nearness, this endless crossing, that calls forth the inner translator—the one who moves tenderly at thresholds, carrying meaning from one shore of being to the next. All that is luminous in translation is born in such respect for strangeness, for the gentle aperture that never quite closes between knower and known.

If the untranslatable is not a failure; it must be the exquisite invitation to live in the possibility of the in-between, to let the world slip out of your grasp and discover, fingers open, the gentle width of imagination. Imagination is the only place on earth where all places are. It also a country whose borders are always in flux. Some discover its provinces often, not by effort or skill, but by suspicion—a quiet, growing intuition that reality, even as it appears, is only suggestion. “You have unfathomable powers of translation over it,” says the inner voice that sometimes saves us.

There is a lingering suspicion, beneath every experience, that the end of the world as we know it is, in fact, a possible destination: and, if it is endings that are always open, perhaps it is only beginnings that remain closed.

So, somewhere in our conscious life, quiet moments unfold us into becoming. We translate meaning, in its deepest and most human sense, as an act of devotion: an ancient practice of binding time to something we cannot know. But this faculty we call imagination becomes the diaphanous membrane through which reality passes and emerges transformed, luminous and more itself for its journey.Through repeated acts of translation, the world’s Babel, its turning dusk, its gestures and sounds move through us with gentle permeability. We witness multiplicity dazzling and infinite, yet unified by perpetual translation. The heart, learning hospitality, opens its petals for whatever comes. Mind traverses patterns, savoring resonance, never insisting it is owned. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, the soul acquires new textures. It gathers the garments of experience, learns to inhabit possibility, and in time discovers itself dressed in the invisible, expansive winds of understanding.

When imagination becomes an interior chapel—quiet, steadfast, lit by the hush between thoughts—it gradually opens its doors to the secret congregants of knowing. It is here, in this chapel’s patient stillness, that the heart’s language is learned: a listening far deeper than the mind’s cleverness, a waiting that lets the world announce itself in slow syllables. A poem, a line, a painting—the breathless pause that recovers what was lost. The necessary is usually impossible to name.

From within this attentive hush, a new truth unfolds: in the heart’s presence, everything is endlessly available. What matters most is the capacity to travel—not only within the intricate halls of the self, but outward and inward, spiraling further from, and then closer to, the liminal seams of reality and imagination. Sometimes, the way back into shared truth is found only by surrendering expertise, by stepping beyond the world’s familiar edge into wild, unmapped terrain.

We become, then, the translators of the heart: builders of bridges not just between words but between ways of being. Take half a step out of the world, and you may arrive in that hidden province, the far-off country where the heart’s knowing can be rendered at last into something living. Let the real strike and go, let something inside shudder and crack—the sensation is the same as being born. The vastness that waits just beyond knowledge is a kind of quiet redemption. It cannot move into the ordinary; it asks only for the courage to enter the new, to breathe the dream. The dream, after all, need not be extraordinary, nor even loud.

Without leaps of imagination, or dreaming, we lose the excitement of possibilities. Dreaming, after all, is a form of planning.

-Gloria Steinem

Dreams come—sometimes fish darting below waking water, sometimes the slack shape of undiscovered country; time settles like gentle dust, odd pairs wore truce in luminous grass. Such dreams neither invented nor found out, persist in their cadence, never disguising, never fully surrendering. Their refusal to coincide with waking world reveals those places the mind vaguely remembers.

There are days, inevitable as dusk, when you find yourself at the uncertain threshold between worlds. It is the hour of departure for some mythic landscape—a country of olives and sun, perhaps, or some imagined latitude that has no name. In that hour, everything cherished clings to you with the weight and stickiness of thought, the mind dense and crowded, unwilling to be set down. This is the knowing mind’s gravity: hefty, deliberate, each idea tugging at your heels.

But just as the air feels airless, a change arrives—gentle, almost unnoticed—a feathery breeze through an open window or the scent of something blooming out of season. A tree of white blossoms unfolds above your ordinary bed, every petal spinning through wind and wonder, and then—suddenly—the impossible shift happens. In the clearing simplicity of yes, you sense the body’s lightness, your hands shedding their utility, becoming birds.

The mind, startled by release, utters its astonished refrain: Oh, I see. Again and again, as blossoms whirl and settle, the mind relents, learning to perceive with a gentler, more porous gaze. And if you return, as the yearning heart inevitably does, to kneel beneath that blooming tree—if you watch the yellow hearts of its flowers shining—a profound quiet gathers. Somewhere inside, quieter and deeper than language, you begin to listen so intently you feel the world dream through you.

Given enough time, this listening ripens into a speaking—not of certainty, but of gentle witness. In that unfinished flowering is the wisdom of the imagination: it does not strive for perfect translation. It chooses, again and again, to remain open, to blossom unfinished—trusting that incompletion is itself the truest form of transformation.

There is joy in knowing the myth of genius is forged so quietly in our own keeping. Even in sleep, the mind spins new realities, undeterred by the night’s impartiality. To dream is no small skill. The body risks all for its blessing, seeking only the fragile bloom of an inward poem. The mind’s greatest faculty is exercised in secret, shaping what daylight disavows. In the dark, it remembers its calling.

There is space, always, for the translation that remains incomplete—for the blossom and the breeze to do their work as they will. This is the most faithful accomplishment: a possibility forever unfinished, a world that is always quietly beginning.

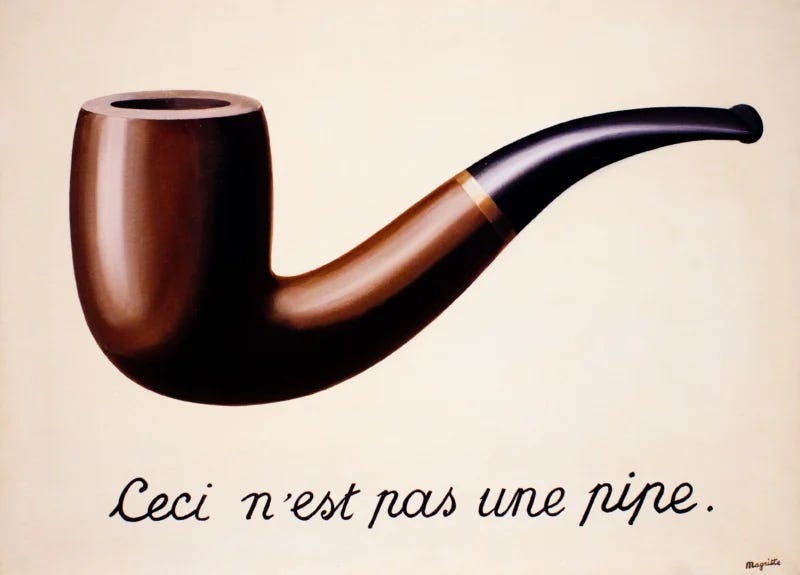

For, in translation, there is always a remainder the sentence can’t quite carry. That edge is the very place where non‑attachment begins: hold the meaning, let go of sameness. Borges, sitting at the edge of the Aleph, knows the despair: symbols can only reference, not embody, the infinite simultaneity of experience.

I arrive now at the ineffable core of my story. And here begins my despair as a writer. All language is a set of symbols whose use among its speakers assumes a shared past. How, then, can I translate into words the limitless Aleph, which my floundering mind can scarcely encompass? Mystics, faced with the same problem, fall back on symbols: to signify the godhead, one Persian speaks of a bird that somehow is all birds; Alanus de Insulis, of a sphere whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere; Ezekiel, of a four‑faced angel who at one and the same time moves east and west, north and south. (Not in vain do I recall these inconceivable analogies; they bear some relation to the Aleph.) Perhaps the gods might grant me a similar metaphor, but then this account would become contaminated by literature, by fiction. Really, what I want to do is impossible, for any listing of an endless series is doomed to be infinitesimal. In that single gigantic instant I saw millions of acts both delightful and awful; not one of them occupied the same point in space, without overlapping or transparency. What my eyes beheld was simultaneous, but what I shall now write down will be successive, because language is successive. Nonetheless, I’ll try to recollect what I can.

Each of us eventually discovers the ache that comes from fastening our lives too tightly to a single map, a single story. When the grip tightens, suffering grows dense and intricate, shaping the self into hard outlines of craving and aversion. The mind, eager for certainty, begins to mistake its own habits for the whole of the world.

Translation teaches another gesture—one that loosens, softens, pulls at the seams. The old wisdom says letting go gently unravels the knot of self; a slow, attentive unweaving. The landscape of reality shifts with every way of looking, every name, every moment of release. Even attention, that vigilant sculptor, is another thread in the weave: every act of noticing, every careful gaze, is already the making of a new world.

To translate well is to become intimate with the motion of making and unmaking. Sometimes the task is to fabricate less, sometimes simply to do it differently, sometimes to surrender all making to something larger. Freedom often waits within a gentle understanding of this pattern—the insight that liberation comes from seeing how the pattern itself forms and dissolves. Encountering art, inhaling poetry before sleep, touching the ache or sweetness in the chest: all these are moments of rare translation, made luminous and strange by the fullness of attention they receive.

A painting glowing at dusk, a poem that arrives as a hush before bed, the secret fire that lights up the ordinary—these crossings, each unfinished, summon the soul to a meeting of worlds. Art gives form to the dream that cannot quite settle in language. Every encounter with imagination is quietly double: a flicker of estrangement and a breath of homecoming, twinned in a single act. And in the larger story—where branches multiply and the ambitions of philosophy scatter the wind—somewhere in the midst of longing and disorder, translation becomes the gentle coordination the world cannot do without.

In the unclaimed space, something stirs—proof that whatever beauty, order, or strangeness we find, this too is the evidence of being alive. The world is confounding, comforting, mysterious. The dream belongs to those who press their lips to its water and, for a fleeting moment, live.

So come to the pond, or the river of your imagination, or the harbor of your longing, and put your lips to the world. And live your life.

—Mary Oliver, Mornings at Blackwater